ETHICS: The Ongoing Failed Application of Utility in Cybersecurity

An Ethical Exploration

…A Faulty Application of Utilitarianism in Cybersecurity….

Utilitarianism is foundational to the Western business ethical decision-making process (Paik, Lee, & Pak, 2019). It is commonly applied in Western commerce to determine corporate risk responses to include the dangers to Information Technology (IT) systems and infrastructures by cyber-threats. Its application will always begin with individual developers, and cybersecurity professionals charged with creating secure systems for a company or a government customer (Scharding, 2019). This articles explores how utilitarianism, as an ethical framework, may be contributing to the long-term failures of Risk Management (RM) cybersecurity practices exercised within the United States (U.S.) federal government.

John Stuart Mill’s and Jeremy Bentham’s classic works in utilitarian thought focus on the impacts of happiness in practical approaches to ethical decision making. Broadly, creating the maximum amount of joy for the society, or customer group, is considered a conclusion to both moral and ethical behavior by individuals. While Paik, Lee, and Pak (2019) offer a more refined definition centered on actions and consequences impacting decision making. They also provide a crucial dichotomy that hints to why certain forms of utilitarianism may be unethical and even lead to weaknesses in the creation of secure IT systems. This article also attempts to answer why there is an inherent qualitative vulnerability of specific utility approaches that prevent modern-day cyber-defenders from being successful against global cyber-threats.

Ethical Dilemma

The dilemma that is posed by applying a pragmatic approach that maximizes happiness to society has been less than adequate. Using the limited definition of classic utilitarianism as espoused by Mill or Bentham to attain the greatest happiness is an illusory model to successful cyber-defensive measures. Cyber-attacks continue against the government and corporate IT infrastructures, and indeed, there is minimal happiness when these assaults occur.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Risk Management Framework (RMF) process has been in place since February 2010 for the federal government (National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST], 2010/2018). NIST establishes standards for cybersecurity protection measures using what are described as security controls aligned with certain security areas such as access control and physical security (NIST, 2010/2018). The problem raised is whether NIST principles and guidance of RM are ethical and effective. Additionally, does the prevalent decision-making model of utilitarianism contribute to added security shortfalls allowing threats to exploit security weaknesses? The mostly qualitative assessment by cybersecurity specialists is whether an IT system is secure may be a critical reason that NIST cybersecurity requirements do not appear to reduce threat successes (NIST, 2010/2018).

Federal IT systems are penetrated and exploited regularly (Allyn, 2019; Olson, 2012; Starr, 2015; Stoll, 2005). The RMF process is seemingly flawed because it continues to fail against cyber-intrusions. Additionally, the RMF process was not constructed nor considered affording individual cybersecurity professionals with an ethical construct to make optimal security decisions. The foundational publication for cybersecurity RM is NIST 800-37, Risk Management for Information Systems and Organizations (NIST, 2010/2018), which does not offer an explicit universal methodology. RMF, while a requirement for years, has not evolved to address its ineffective RM approach for a functional cybersecurity decision-making process.

Background

Ongoing cybersecurity threats. Frequent incursions into the critical U.S. IT systems underscore the agile and impactful consequences of cyber-threats globally (Allyn, 2019; Olson, 2012; Stoll, 2005). The 2015 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) security breach was one of the most extensive and damaging exfiltrations of government personnel data in history (Koerner, 2016; Naylor, 2016). Cyber-attacks have negatively affected the purportedly secure IT infrastructures and systems of the DOD. “For nearly a week, some 4,000-key military and civilian personnel working for the Joint Chiefs of Staff [had] lost access to their unclassified email after what is now believed to be an intrusion into the critical Pentagon server that handles that email network” (Starr, 2015, para. 3). The capability to prevent cyber-assaults has of yet not substantially improved (Allyn, 2019; Garamone, 2018; Newman, 2020).

Cyber-thugs repeatedly hack companies and agencies around the globe (Kaplan, 2016; Olson, 2012). Computer attacks happen to even the most technically capable companies such as Eurofins, a United Kingdom’s (U.K.) based company in 2019 (Devlin, 2019; Olson, 2012). Eurofins paid an undisclosed amount of money to hackers to regain access to their databases’ and records’ repositories; this information was vital to Britain’s primary criminal forensics support firm to the multitude of the U.K.’s law enforcement agencies (Devlin, 2019). Technically adept organizations fail against cyber-assaults even with the application of international cybersecurity measures similar to those employed by the U.S.

Utilitarian thought. As individual cybersecurity specialists apply the principles of utilitarianism in their understanding and assessment of the rules of RMF, they regularly fail. Exploring the foundational leaders of utilitarianism to include John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, the ethical application of classic utilitarianism identifies critical shortfalls in the most commonly used approaches to governmental decision paradigms (Paik et al., 2019). Classic utilitarianism may not be affording the maximum or at least optimal reduction of cyber-threat victories.

Mill’s “theory of utility” offers some explanation for the unsuccessful implementation of utilitarianism (Mill, 1861, as cited in Lindebaum & Raftopoulou, 2017, p. 813). In one of Mill’s corollaries, he suggests that individuals pursue “the prevention of pain” even more significantly than their pursuit of happiness (p. 814). His work may indicate a humanistic reason where cyber-professionals are risk-averse and do not want to clash with their superiors and peers to avoid the discomfort of conflict (Auerswald, Konrad, & Thum, 2018).

Another noted scholar of utilitarianism is Bentham. He stated that “[i]t is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of [moral] right and wrong” (Bentham 1776, as cited in Hollander, 2016, p. 557). Bentham’s axiom also offers an insight into where utilitarianism most likely fails; making the most significant number of people happy is not necessarily a prescription for reliable security measures. Cybersecurity specialists are humans that want to be liked and make others happy by confirming that, for example, an IT system is entirely secure. The natural implications of classic utilitarianism may be contributing directly to the difficulties of defending IT systems.

Values, Laws, Rules, Policies, and Procedures Violated

There are three reasons that RM and the application of certain forms of utilitarianism are inadequate. First, is the assumption that the root cause failures of poorly designed IT systems rest with the individual alone—be it the Information Systems Security Officer (ISSO), the Information Systems Security Engineer (ISSE), or the respective defense company system developer (Malhotra, 2018). This subconscious perception, as discussed by Malhotra (2018), is that it is not only flawed but creates added societal and senior pressures for the cybersecurity professionals. Secondly, the NIST standards are often violated by intention or neglect. Further, NIST has not provided the associated means and enterprise risk management solutions for success to include weak implementation by an ill-defined or missing governance process (Elango, Kundu, & Paudel, 2010; Lackovic, 2017; NIST, 2010/2018).

Finally, the gravest violation occurs when individuals and companies assert that the work delivered to the government is secure and complies with cybersecurity standards and does not. The False Claims Act (FCA) of 1863 is beginning to play a decisive role in punishing unfulfilled defense contract work. There are certainly more reasons for cybersecurity RM’s inadequacy, but these areas offer crucial insight into why it continues to falter.

Human error as a superficial fault. At the most basic level, human beings seeking utilitarian happiness to apply cybersecurity requirements, to include, RMF, will predominantly attempt to avoid any strife in rendering a positive and secure outcome for the government customer (Lindebaum & Raftopoulou, 2017). The real values that should be pursued are standardized security control effectiveness that protects the societal element, such as the federal government and U.S. taxpayers (Paik et al., 2019). The values that are violated are a result of the individuals’ need to belong to the society of other cybersecurity experts and workplace specialists, as best described by Maslow’s (1943) famed work on the Hierarchy of Needs. It is this conflict between making others happy with the unethical situational results of secure system design or pressing for the difficult right; this is what makes moral and ethical decision making complicated (Tran, 2008). Human beings prefer to avoid disagreement, and this happens even in the application of cybersecurity protection measures.

Malhotra (2018) suggests further that an organization’s leadership will most typically assign the root cause of their risk-based analysis and results to “employee behavior” (p. 43). In other words, while RM does rest with every individual in the society, it is a poor assumption to ascribe the failure to just a singular corporate individual or individuals alone (Stahl, 2004). “[T]rue root causes are buried beneath multiple layers of causal factors” that should not just be an issue of human error (Malhotra, 2018, p. 43).

While individuals may contribute to poor cybersecurity preparation, defense business entities are typically bound by contract to meet NIST cybersecurity standards in the U.S.; when they fail, they should receive the majority of any penalty financially or reputationally. While the individuals may be at direct fault for shortfalls in security implementation, there remains a need for “collective responsibility” to include the corporation (Scharding, 2018, p. 941).

Further, the breakdown to be considered in cybersecurity may also be suggested by not conducting proper Root Cause Analysis (Malhotra, 2018; Susca, 2018; Tomlinson, 2018). Tomlinson (2015) emphasizes that it is not the environmental conditions or individuals’ behaviors, “but rather the dysfunction within the operation that allows that condition or behavior to exist” to include the weak or non-existing application of security measures (p. 52). The principles that prevent cybersecurity professionals from being successful include that the “operators [cyber-professionals] must have the tools and coaching to lead them through the process” (p. 52).

It is not necessarily that utilitarianism has utterly failed as an ethical approach, but the human nature that makes it difficult for the cyber-professionals and developers to create secure IT systems that apply the wrong form of utilitarian thought and action. The objective should be to conduct a rule utilitarian effort that determines whether controls are sufficient. Rule utilitarianism is best described as a “framework for making choices and for acting in ways that will generally produce the best consequences for all affected parties” (Paik et al., 2019, p. 842). However, any framework must be unambiguous and be standardized by a governance method that accomplishes definite ethical and effective outcomes (Tran, 2008).

RMF and NIST 800-37. In 2014, the DOD mandated that all DOD agencies transition from the legacy Defense Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process (DIACAP) to RMF (Department of Defense [DOD], 2017). This was an effort to standardize the implementation of the NIST security controls for the entirety of the federal government. RMF establishes processes and procedures to defend IT systems through the rigors of hundreds of specified security measures implemented and assessed by individual experts.

Specific security controls are how individuals, such as the ISSO, ISSE, and typically, the defense contractors’ system developers, build new and secure systems for the federal government. These subject matter experts then use their technical knowledge and the organizational governance processes to document what controls are met or not; this remains a significant weakness across much of the federal government. The absence of a well-functioning governance process for the government is an acute systemic root cause failure of RMF.

Cybersecurity professionals may apply an act or rule utilitarian approach (Paik et al., 2019). As described earlier, the objective should always be to use rule utilitarianism in the cybersecurity RM review and assessment process. Conversely, act utilitarianism is described as “situation ethics,” where it is based upon the context of the event by the individual (p. 842). Unfortunately, this form of utilitarianism has no standards or norms, which leaves much of the determinations to the cybersecurity specialist without any support from senior leadership and a deficient governance process (Elango et al., 2010). The absence of a proper and functioning governance body adds to the breakdown of effective cybersecurity (NIST, 2010/2018).

Additionally, it is a cumulative failure that makes it difficult for cybersecurity experts to conduct their work. The severest failure of most of NIST policy standards and guidance is that it only provides what to do and not how to accomplish the security of the system via a security control (Russo, 2018). The security experts or assessors have had to be expeditious in completing their assessment vice considering the effects of a failed control to meet critical delivery milestones and timelines for the government customer. Ultimately, the actions of the system developer (and the defense contractor) are assessed by cybersecurity professionals who recommend to the Authorizing Official (AO) whether the system is secure based upon RMF control implementation; that has been historically more art than science.

The shortfall is more of aggregate deficits of the recommended NIST cybersecurity process that cause cyber-professionals to provide incomplete security oversight and direction. As mentioned earlier, the DOD mandates that RMF be met in the delivery of secure systems to the government. If the government neglects to create a viable governance process and the cyber-experts fail to defend, for example, their recommendations of security impacts, the society, the government, and contractors all suffer when the system is compromised (Elango et al., 2010).

False claims act. Fraud against the government by defense contractors is often pursued under the FCA. This is the primary law the U.S. federal government uses to address contract fraud when the contractor makes a false claim of the actual delivery of a final product or service. If the government determines a contractor has not met its contractual obligations, it may be subject to FCA prosecution (Department of Justice [DOJ], 2020).

A hallmark case was decided on May 8, 2019, in the Court for the Eastern District of California that was decided in favor of the plaintiff, Mr. Markus. Markus was not a government official; however, the government entered into his case as an interested party. This case was the first time the FCA was applied in a matter affecting U.S. cybersecurity contractual obligations by a defense contractor.

Markus was not willing to hide a known cybersecurity fraud event and would not affirm that his company was fully compliant with its federal cybersecurity requirements. He was also the defendant’s former Director of Cybersecurity and was not interested in participating in this scam. In U.S. ex rel. Markus v. Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings Inc. (2019), Markus alleged that Aerojet did not meet minimal federal cybersecurity standards required under the contract (U.S. ex rel. Markus v. Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, 2019).

Additionally, Aerojet Rocketdyne had hired an outside, independent security firm to review its security control implementation of a system for both the DOD and National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA). Markus was aware of the findings of that assessment. The assessors determined less than 25% of the security controls were implemented (U.S. ex rel. Markus v. Aerojet Rocketdyne, 2019). The resulting win by Markus likely signals the FCA as the legal instrument of choice that the government will employ against flawed contractors in the realm of cybersecurity. This was the first time the FCA played an indirect, but no less impactful, role in future federal cybersecurity litigation.

Further, the government entered the case ex rel. Ex rel is where there is a significant interest in a situation that impacts relationships with other legal parties to include the protection of IT systems and networks (Law.com, 2020). The government had explicitly expressed its concern in the case by joining it based upon the importance is resolving ongoing challenges with implementing cybersecurity measures across the government; they could not merely ignore this case. While there are certainly more developments to occur in cyberlaw enforcement, this 2019 case implies that the federal government has identified the FCA as a means to address cybersecurity violations for the future.

The Process Resolution

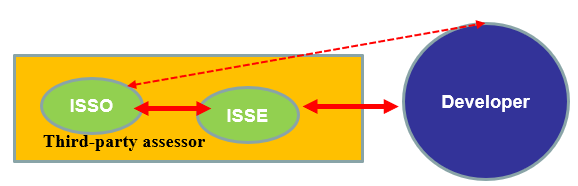

The process, as generally described by NIST 800-37, relies upon three initial leading cybersecurity specialists in implementing and assessing the state of any IT system delivered to the government. The ISSO and ISSE are usually part of an independent third-party assessor team that affords the expertise to execute NIST standards. They provide the quality control and technical oversight of the contract developer and his team of engineers, architects, and programmers. The developer also assigns its own ISSO to create the documentation and work with other development team members to collect critical information about security control implementation (NIST, 2010/2018).

Initially, the ISSE works with the developer to provide technical direction and guidance to ensure the system is securely built. The ISSE should be part of the initial requirements process and consulted throughout the progressive lifecycle; however, that seldom happens. Once the system is near-ready to become operational, usually by connecting to DOD networks and infrastructures, meetings are conducted to review the assessment package (NIST, 2010/2018).

The ISSO is the independent assessor and prepares to evaluate the system and to coordinate with the ISSE and the development team. The ISSO will work with the ISSE to confirm before the formal assessment that the system is secure, that all security documentation is complete, and any plans of action and milestones are acceptable. The ISSO then performs a formal assessment and may have other ISSOs and ISSEs assist in the evaluation based on the size and complexity of the system to be accredited. Based on the results of this evaluation, controls will be assessed as pass or fail, and the results will be collected in a final system security report for the AO (NIST, 2010/2018).

The AO is the final approval authority and is the key individual in the process. The AO, based upon the recommendation of the ISSO, will accept or deny the ISSO’s advice and make a final determination to issue an Authority to Operate (ATO). An ATO affirms to other AOs and technology owners that the system is secure and can be connected to DOD networks or other components of the infrastructure. Overall, the AO is the risk manager who accepts any residual risk and tracks it with the help of the ISSO and ISSE to afford continuous monitoring during the entirety of the system lifecycle (Lackovic, 2017).

Pros of the process. The positives of this process are it is well-established based upon other industries that require RM in their arenas to include, for example, banking, finance, and medical (Pham, 2018; Weng, 2017). RMF provides a standardized identification of security controls and also includes needed flexibility to accommodate the complexity and security requirements of the federal government. Also, there is a multitude of supporting publications and guidance that NIST regularly produces focused on cybersecurity to include, for example, an updated version of NIST 800-37 revision 2 in 2018.

Cons of the process. The negatives are more a failure of leadership at all levels of the government and contracting community to establish a multi-tiered governance process as defined by NIST 800-37; this is the presumed root cause failure based upon this paper’s analysis of the problem (Susca, 2018). The DOD, in actuality, has done the best job in attempting to create limited guidance to its cybersecurity support specialists. However, the failure is that there is an ongoing treatment of cybersecurity as an IT and not as a strategic corporate function to be managed by executive leadership (Rothrock, Kaplan, & Van Der Oord, 2018). Managers focus on “keeping hackers out [which is reactive]…rather than [being proactively focused on] building resilience” (p. 13).

The difficulties also result within the process when the executives have to weigh the challenges of operational delivery to meet milestones versus security considerations–security often assumes second place within this typical balancing act.Furthermore, it is for additional reasons such as a “prevailing culture [of]…blame and negative consequences, most employees [to include cybersecurity specialists] will hide real or potential sources of risk” (Kendall, 2017, p. 5). Complex and adverse work environments contribute to and create obstacles leading to act utilitarianism as a likely mystery culprit for much of the failures of cybersecurity. This form of utilitarianism may explain the predominant reason that individual cyber-experts repeatedly fail against cyber-attacks.

Other Potential Outcomes and Changing Behaviors

Other positive potential outcomes will occur when the individual leaders become engaged in the procedure to include, especially the governance process. If the AO and other leaders formally develop a defined method to address how corporately specific controls should be met, cyber-threats would likely be less effective. When cybersecurity governance methodologies evolve to defining security measures for all applicable controls, this will move the assessment effort from being speculative and qualitative to a truly rule-based ethical effort to minimize cyber-threat effectiveness (Elango et al., 2010).

Tran (2008) suggests that ethics at the corporate level is both problematic and ambiguous; it is just as challenging at the individual level. There are obstacles in changing the behaviors of cybersecurity professionals to be focused more on consequences than their classic utilitarian happiness. As Tomlinson (2015) mentioned earlier, these individuals need the tools, training, and corporate championship to emphasize that the governance process uses a rule utilitarian approach to avoid ambiguity and comport with an effective and ethical mindset (Elango et al., 2010; Tran, 2008). Requirements would allow cyber-experts to apply senior leadership’s categorization of what constitutes a pass or fail and would ensure that IT system security is optimized (Lackovic, 2017).

Conclusion

Lackovic’s (2017) literature review highlights that “existing research is theoretical and more empirical research is missing” in the application of RM in the real-world (p. 369). She posits that RM needs to be less vague in its approach, and more quantitative and defined measures are required to address the continual challenges of cybersecurity. Rule-based utilitarianism is not the only solution to this task; however, it is needed to avoid the ongoing humanistic survival mode of the cybersecurity professionals trying to implement secure systems. It requires a universal attitude across an organization and the government collectively to accomplish active cybersecurity system development.

Individuals are the foundation of any ethical application. However, it requires a collective effort with the right ethical model and an environment that allows for constructive conflict that better ensures secure IT systems (Chowdhury & Shil, 2019; Scharding, 2018). Until senior leadership allows for productive criticism and the allowance for diverse opinions, cyber-threats will continue to exploit the qualitative shortfalls of RMF.

References

Allyn, B. (2019, August 20). 22 Texas towns hit with ransomware attack in ‘new front’ of cyberassault. National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/08/20/752695554/23-texas-towns-hit-with-ransomware-attack-in-new-front-of-cyberassault

Auerswald, H., Konrad, K. A., & Thum, M. (2018). Adaptation, mitigation, and risk-taking in climate policy. Journal of Economics, 124(3), 269–287. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1007/s00712-017-0579-8

Chowdhury, A., & Shil, N. C. (2019). Influence of new public management philosophy on risk management, fraud and corruption control, and internal audit: Evidence from an australian public sector organization. Accounting and Management Information Systems, 18(4), 486–508. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.24818/jamis.2019.04002

Devlin, H. (2019, July 5). Hacked forensic firm pays ransom after malware attack. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/jul/05/eurofins-ransomware-attack-hacked-forensic-provider-pays-ransom

Elango, B., Paul, K., Kundu, S. K., & Paudel, S. K. (2010). Organizational ethics, individual ethics, and ethical intentions in international decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 543-561. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=29ec82ab-2239-4846-a80c-15cf994ce180%40pdc-v-sessmgr03

Ex rel. (2020). In Law.com dictionary. Retrieved from https://dictionary.law.com/Default.aspx?selected=705

Garamone, J. (2018, February 13). Cyber tops list of threats to U.S. director of national intelligence says. Defense.gov. Retrieved from https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/News/Article/Article/1440838/cyber-tops-list-of-threats-to-us-director-of-national-intelligence-says/

Hollander, S. (2016). Ethical utilitarianism and the theory of moral sentiments: Adam smith in relation to hume and bentham. Eastern Economic Journal, 42(4), 557–580. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1057/s41302-016-0003-z

Kaplan, F. (2016). Dark territory: The secret history of cyber war. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Kendall, K. (2017). The increasing importance of risk management in an uncertain world. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 40(1), 4–8. Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/1895913339?accountid=44888

Koerner, B. (2016, October 23). Inside the cyberattack that shocked the US government. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2016/10/inside-cyberattack-shocked-us-government/

Lackovic, I. D. (2017). Enterprise Risk Management: A Literature Survey. Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency (VADEA). Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/2070393421?accountid=44888

Lindebaum, D., & Raftopoulou, E. (2017). What would john stuart mill say? A utilitarian perspective on contemporary neuroscience debates in leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(4), 813–822. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1007/s10551-014-2247-z

Malhotra, S. (2018). Behavioral assumptions in root-cause analysis. Professional Safety, 63(1), 43-44. Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/1985534144?accountid=44888

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. York University. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm

National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2010/2018). Risk management framework for information systems and organizations A system life cycle approach for security and privacy (NIST 800-37 revision 2). Retrieved from https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-37r2.pdf

Naylor, B. (2016, June 6). One year after OPM data breach, what has the government learned? National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/06/06/480968999/one-year-after-opm-data-breach-what-has-the-government-learned

Newman, L. (2020, April 14) The pentagon hasn’t fixed basic cybersecurity blind spots. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/pentagon-cybersecurity-blind-spots/

Olson, P. (2012). We are anonymous: Inside the hacker world of LulzSec, Anonymous, and the global cyber insurgency. New York, NY: Little, Brown, and Company.

Paik, Y., Lee, J. M., & Pak, Y. S. (2019). Convergence in international business ethics? A comparative study of ethical philosophies, thinking style, and ethical decision-making between US and korean managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(3), 839–855. Retrieved from doi: http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1007/s10551-017-3629-9

Pham, T. M. (2018). Exploring strategies for incorporating population-level external information in multiple imputation of missing data (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from EBSCO Open Dissertations. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ddu&AN=788945D34A68B6CD&site=ehost-live

Rothrock, R. A., Kaplan, J., & Van Der Oord, F. (2018). The board’s role in managing cybersecurity risks. MIT Sloan Management Review, 59(2), 12–15. Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/1986317468?accountid=44888

Russo, M. (2018). NIST 800-171: Beyond DOD. Independently published (Amazon).

Russo, M. (2020, June 5). Personal interview.

Scharding, T. (2019). Individual actions and corporate moral responsibility: A (reconstituted) kantian approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(4), 929–942. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1007/s10551-018-3889-z

Stahl, B. C. (2004). Responsibility for information assurance and privacy: A problem of individual ethics? Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 16(3), 59–77. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.4018/joeuc.2004070104

Starr, B. (2015, July 31). Military still dealing with cyberattack’ mess.’ CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2015/07/31/politics/defense-department-computer-intrusion-email-server/index.html

Stoll, C. (2005). The cuckoo’s egg: Tracking a spy through the maze of computer espionage. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Susca, P. T. (2018). How healthy are your risk management programs? Professional Safety, 63(10), 24–26. Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/2117115633?accountid=44888

Tomlinson, R. (2015). Root-cause analysis: Analyze, define & fix. Professional Safety, 60(9), 52–53. Retrieved from https://franklin.captechu.edu:2074/docview/1709999331?accountid=44888

Tran, B. (2008). Paradigms in corporate ethics: The legality and values of corporate ethics. Social Responsibility Journal, 4(1), 158–171. Retrieved from doi:http://franklin.captechu.edu:2123/10.1108/17471110810856929

U.S. Department of Defense. DOD Chief Information Office. (2017, July 28). Risk management framework (RMF) for DOD information technology (IT) (DOD Instruction No. 8510.01). Retrieved from https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/851001p.pdf?ver=2019-02-26-101520-300

U.S. Department of Justice. (2020). The false claims act. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/civil/false-claims-act

United States ex rel. Brian Markus v. Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, 381 F.Supp.3d. 1240 (U.S. District Court, Eastern District California 2019). Retrieved from https://casetext.com/case/united-states-ex-rel-markus-v-aerojet-rocketdyne-holdings-inc

Weng, B. (2017). Application of machine learning techniques for stock market prediction (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from EBSCO Open Dissertations. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ddu&AN=DE0B8B4C2E217AE3&site=ehost-live

Dr. Russo is currently the Senior Data Scientist with Cybersenetinel AI in Washington, DC. He is a former Senior Information Security Engineer within the Department of Defense’s (DOD) F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program. He has an extensive background in cybersecurity and is an expert in the Risk Management Framework (RMF) and DOD Instruction 8510, which implement RMF throughout the DOD and the federal government. He holds a Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) certification and a CISSP in information security architecture (ISSAP). He has a 2017 Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) certification from the National Defense University, Washington, DC. Dr. Russo retired from the US Army Reserves in 2012 as a Senior Intelligence Officer.