SERIES: Virtual Evidence & Challenges in Cyberlaw

PART 1: The Benefits & Dangers to Law Enforcement (LE)

BACKGROUND

The Washington Post Magazine (Sellers, 2015) described a fictional child abduction case where the perpetrator was apprehended through the use of linguistic forensics, computer search technologies, and a thorough understanding of online underground market places. Law Enforcement (LE) was able to rescue a kidnapped young girl by employing a series of effective keyword searches based on a unique linguistic expression by an uncooperative relative and the prime suspect. While the power and capabilities of the Internet are vast, they are not the ultimate “silver bullet” alone; it requires a breadth of LE knowledge and capabilities. No one approach can be relied upon as complete and definitive for solving crimes and ensuring admissibility by the courts in criminal investigations.

The Information Age affords a new modality of evidence that can improve the capabilities of modern-day LE techniques and approaches. The desire is that virtual evidence, such as Internet Protocol (IP) addresses on an electronic mail header, for example, be incontrovertible in determining attribution of a particular perpetrator; that is neither likely or possible. Just as physical evidence such as blood,hair, and DNA evidence can be surreptitiously introduced, modified, or destroyed, the same can occur with virtual evidence extracted from computers and their network communications.

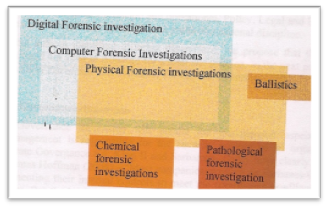

This requires an expanded view of evidence in a multi-source or multi-dimensional perspective. The forms of evidence (physical and virtual)should be used to confirm the violation of law. Leveraging differing evidentiary modalities such as physical evidence should be used to confirm virtual evidence and its findings, and vice versa. In the paper, Digital Forensics: A Multi-Dimensional Discipline, the authors emphasize that there are numerous dimensions to Digital Forensics (DF); “…the dimensions are interrelated and should not exist in isolation for a total…solution,” (Grobler & Louwrens, 2006, p.3). DF is only a part of the overall evidentiary setting;it must be complemented by physical evidence and traditional LE best practices and techniques to ascertain the criminality of an individual or individuals.

MULTI-SOURCE MODALITY OF EVIDENCE

The Information Age provides new technical types of evidentiary components such as IP addresses, Media Access Control addresses (the hardware’s serial number in cyberspace), and hashing values (file“fingerprint” information) for LE’s ability to fight crime. While these add additional complexity and challenge to classic detective work, they also help to enhance LE’s capacity to better investigate crime overall. The description in the 2006 paper on Digital Forensics: A Multi-Dimensional Discipline, the authors provide a model of the current facets of both digital and physical forensic investigations. Figure 1 (Grobler & Louwrens, 2006,p.2) provides a visual representation of the overlap between physical and computer forensics. Further, Digital Forensics (DF) extends beyond the physical instrument of the computer to the digital network (i.e., the Internet). This Forensic’s Investigation Landscape (Figure 1) collectively includes computer forensics which is the physical computer and its local hardware and software components. DF composes the transitory data and communications that travels the global Internet from the respective computer. Together all of these elements provide a holistic model for investigators to focus their expertise and provides the framework for attacking the investigatory landscape.

Figure 1 -Forensic Investigation Landscape

It is important to understand these relationships focus LE resources during the investigation of a crime. The ability to correlate vital elements of evidence in cyberspace is as important to an investigation as the classic forensic efforts in the physical world. This understanding and validation of multiple sources of evidence has other analogies as in news reporting and the intelligence arena to ascertain fact from fiction.

The Intelligence Community (IC) offers a parallel example of how multi-modal or multi-source evidence is used to verify facts. In the case of intelligence, it is understood that no one source is totally reliable. It is through the application of multiple sources of collection capabilities that one can have improved certainty of a fact from the available technical and human sources. While imagery collection may be impaired by an underground facility preventing the ability of a U-2 “spy” aircraft from acquiring photographic evidence, another source, such as human intelligence, may be able to infiltrate a suspected nuclear facility and confirm its nefarious activities.

Joint Publication 2-0, Joint Intelligence,states: “[t]o minimize the effects of enemy deception, and provide the … most accurate intelligence possible, analysis of information from a variety of collection sources is required so information from one source can be verified or confirmed by others,” (Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013, I-14). The IC’s use of multiple sources of evidence provides a good direct comparison for LE in its usage of both virtual and physical evidence.

|

SIGINT: Signals Intelligence: intelligence

produced by exploiting foreign communications systems and non-communications

emitters. GEOINT: Geospatial Intelligence: exploitation and analysis of imagery and geospatial information to describe, assess, and visually depict physical features and geographically referenced activities on the Earth. HUMINT: Human Intelligence: derived from information collected and provided by human sources. OSINT: Open Source Intelligence: based on open source information that any member of the public can lawfully obtain by request, purchase, or observation. REFERENCE: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013, B-1 through B-7. |

Figure 2 – The Four Major Intelligence Categories

Multi-modal intelligence source collection is as important to LE as the IC. The need to avoid any intentional or unintentional biases needs to be minimized by the right types and kinds of evidence

Next Week: The Legal Frameworks that Support and Stymie LE

References:

Balkin, J., Grimmelmann, J., Katz, E. K., Kozlovski, N., & Wagman, S. e. (2007). Cybercrime: Digital Cops in a Networked Environment. New York City: New York University Press.

Clarke, R. A., & Knake, R. K. (2010). Cyber War.New York: Harper-Collins Publishers.

Cornell University. (2012, January 4). 42 U.S. Code § 2000aa – Searches and seizures by government officers and employees in connection with investigation or prosecution of criminal offenses. Retrieved from Legal Information Institute (LII): https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/pdf/uscode42/lii_usc_TI_42_CH_21A_SC_I_PA_A_SE_2000aa.pdf

Grobler, C., & Louwrens, B. (2006). Digital Forensics: A Multi-Dimensional Discipline. Proceedings of the ISSA 2006 from Insight to Foresight Conference. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Joint Chiefs of Staff. (2013, October 22). Joint Publication 2-0: Joint Intelligence. Retrieved from Defense Technical Information Center: http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp2_0.pdf

Leithauser, T. (2010). Experts Urge Caution in Developing New Cyber Attack Attribution. Cybersecurity Policy Report. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.nduezproxy.idm.oclc.org/docview/746442315?accountid=12686

Lutes, K. D., & & Mislan, R. P. (2008). Challenges in Mobile Phone Forensics. 5th International Conference on Cybernetics and Information Technologies, Systems and Applications. West Lafayette: Purdue University.

Mejia, E. F. (2014, Spring). Act and Actor Attribution in Cyberspace: A Proposed Analytic Framework. Strategic Studies Quarterly, pp. 114-132.

Murphy, D. C. (2009). Developing Process for Mobile Device Forensics. SANS Institute. Retrieved from SANS.

Nolan, R., O’Sullivan, C., Branson, J., & Waits, C. (2005). First Responders Guide to Computer Forensics. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon; Software Engineering Institute.

Rhee, H.-S., Ryu, Y. U., & Cheong-Tag, K. (2012). Unrealistic Optimism on Information Security Management. Computers and Security, 221-232.

Robinson, M., Jones, K., & Janicke, H. (2015). Cyber warfare: Issues and Challenges. Computers and Security, 70-94.

Sellers, F. S. (2015, March 1). Different Strokes: What Criminal Investigators are Looking for in our Text and Tweets. The Washington Post Magazine, pp. 19-26.

Steve Jackson Games, Inc., et. al., Plaintiff-Appellants, v. United States Secret Service, et. al., Defendants, United States Secret Service and United States of America, Defendants-Appellees, 93-8661 (US Court of Appeals for the 5th District October 31, 1994).

TechComm (a synthesized drawing from source and paper author). (2010, July 26). Public Key Infrastructure . Retrieved from TechComm : http://tech-writing-space.blogspot.com/2010/07/public-key-infrastructure.html

United States of America v. Howard Wesley Cotterman, 09-10139; DC No. 4:07-cr-01207-RCC-CRP-1 (US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit March 8, 2013).

1 thought on “SERIES: Virtual Evidence & Challenges in Cyberlaw”

Comments are closed.